Ex 3:1-8a, 13-15: I AM sent me to you.

1 Cor 10:1-6, 10-12: We should take care that we do not fall.

Lk 13:1-9: The Parable of the Fig Tree

Liturgists are funny guys: you gotta wonder what they're thinking sometimes when they put together the readings for any given Sunday.

Today, the Third Sunday in Lent, Year C, is one of those times.

At least on the face of it, the common theme is trees. Okay, so maybe a bush and a tree, but you get the point. Moses finds a burning bush. Jesus discusses a fig tree. Plant life. Botany. Is this like a freshman bio joke.?

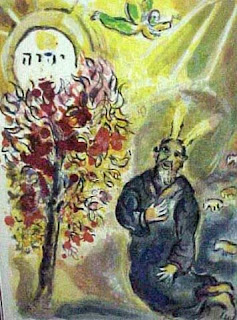

But the stories in themselves are interesting...the parts that aren't really about trees. For instance, when Moses find the burning bush, he's attracted to it. And when he gets close enough, God tells him to take his shoes off. Weird. But there's something significant about that. God, of course, is the original Holy of Holies. Wouldn't someone who was really holy turn his nose up at something that was not-so-holy. And Moses is certainly not-so-holy; he's a virtual Egyptian, after all, and one who's done murder--even the Egyptians won't have him! But God puts a burning bush out there as though he wants Moses to come close. And when he gets too close, God tells him to take his shoes off as though he wants real, direct contact with Moses. I know that in the Middle East of the day, you removed your shoes when you came into someone's home; you didn't want to carry the dirt and the dung of the road inside. But I am struck by the thought that God is not afraid of this direct contact with Moses, and with his feet, for heaven's sake! It's almost as though God wants his holiness to soak into Moses from the very ground he treads, as though God wants Moses to be rooted in his holiness as the bush is in the ground. As though God wants Moses, like the burning bush, to catch fire with his holiness.

The other thing that is striking is about God's name: I AM WHO AM is the traditional translation. It is this God who is always present, in a permanent state of the present tense. No past. No future. Always present. Present to Moses. Present to the Israelites far off in Egypt, stuck in their slavery, for whom God is but memory--the God of the ancestors.

The Gospel is interesting in the same weird ways: Jesus tells the story of a vineyard owner who has a fig tree in his vineyard (weird place for a fig tree!) He looks for fruit and finds none, so he prepares to cut the tree down; after all, it is just wasting the soil and using up space. But his servant says no, give the tree some time. He'll work on it, he says, and fertilize it. And then, well...maybe next year, like the eternal Brooklyn Dodgers fan.

Now many of us immediately assume that there is an easy allegorical interpretation to this story: we are the fig tree, God wants us to bear fruit and we don't so God is angry, but Jesus cuts us a break. But if we read the whole passage--all that stuff about the Galileans slaughtered by Herod and the victims of the Siloam tower collapse--we might get a glimmer of something more. Because the people who tell Jesus about the massacre of the Galileans by Herod assume that there was something wrong with their sacrifice; they assume that God must have been really, really angry with those Galileans. But Jesus says that doesn't make sense. They were killed by Herod, not by God. And the people killed by the tower's fall...they were killed by falling bricks and morter and the laws of gravity. God has nothing to do with it. But then he warns them that they have to repent, or they too will perish.

Weird. Again, weird.

But what does it mean to repent? We all know (or think we know) that repent means turning back to God (it does) and perhaps doing hard things, like giving something up during Lent (it can). But at its root, one of the things repent means is to rethink--to rethink ourselves and our ways, to rethink who God really is, and to rethink our relationship with God. And certainly that is one of the things Jesus needs for these people to do, for just like the scribes and the Pharisees, they have passed a harsh judgment--a harsh judgment about the people caught in these tragedies, and also a pretty harsh judgment about God.

If we look at the Parable of the Fig Tree in this context, the roles suddenly change. We are the ones who are disappointed, we are the ones who make the harsh judgment: Cut it down! It's a waste of time and space and good soil and effort. Enough already. How often do find that attitude in ourselves? We sometimes say that about others, we say that about situations, and most hauntingly, we sometimes say that about ourselves. How many times do we look inward and see how little has changed in us? How many times are we tempted to give up, to let go of our best hopes about ourselves because we know--we know!--they will never be realized? But it is God who says, very concretely in his son's life with and for us: No, let's give it another season. Let's give it another try, and see what happens. And then it is God who works like crazy, who gives his own sweat and blood and tears, to help us grow, to help us to become fruitful.

So really, both readings are really about compassion--the compassion that draws us near and holds us sacred, the compassion that hopes that we will catch fire. The compassion that hears the our cry when we are far-off, enslaved, estranged. The compassion that is always present if we will but turn to accept it. The compassion that gives everything it has--all its labor, all its days which are endless, that we might be holy as he is holy. The compassion that hopes that we will absorb him like a tree absorbs from its roots, so that we can offer the fruits of compassion to all who come to us in need.

That's what Paul is talking to us about in Corinthians too, that we have to learn from the goodness and the generosity of God so that we don't become ungrateful, forgetful, so that we don't make God a thing of our past, but rather that we make him the center of our present. If we can do that, our baptisms will not have been in vain, and all the work that God has done for us will not be squandered. No, we shall reflect him, and reflecting him, become the true sons and daughters he longs to see. We will be compassionate, even as he is compassionate. For like every good father, God hopes to see a little bit of himself in his children. And wehn we are compassionate, he recognizes us immediately!

One last thing that strikes me is that Jesus so often uses agricultural imagery; he grew up, after all, in a world of flocks and farms. And so he often talks of the good earth, the weeds and the wheat, the vines, the sheep that wander. But it is important to remember something about ourselves that I think God remembers each time he looks upon us: the parables are parables, and just that, and that we are not fig trees, or weeds, or dirt, or wheat or sheep. No, we are human, profoundly human, sometimes terribly human. We are dust and clay indeed, but dust and clay into which God has breathed. We may be like vines, but we are like vines connected to a root--to Jesus. And as human beings, we can make decisions that earth and vines and weeds and wheat and sheep can never make; we can choose to be like our Father, loving, forgiving, compassionate. And in the moment we choose so, we are changed. And that is the fruit, a fruit so much better than a fig, that the God looks for. And he, the good gardener, is so glorified whenever, wherever, he sees it in us.

AMDG

No comments:

Post a Comment