At the Procession of the Palms

Luke 19:28-40; "If they keep silent, the stones will cry out!"

At Mass

Isaiah 50:4-7: A Song of the Suffering Servant

Philippians 2:6-11: He emptied himself, taking the form of a slave.

Luke 22:14 - 23:56: "Father, forgive them, they know not what they do."

When I began this blog seven weeks ago, it never occurred to me how hard it would be...

I don't say that for the sake of pity. It is just that the Gospel is a really hard thing when you actually try to make sense of it, when you actually try to pray it. And for Jesus, how hard it must have been to live it.

For that is what he did: he lived the Good News. With all his heart and soul and mind and strength.

We get a sense of that in the contrast between the two moments of the Gospel we hear this Sunday. We begin with the glorious spring morning when Jesus arrives in Jerusalem to the Song of Ascents, typically sung by pilgrims as they arrived in the Holy City. And though the people and the disciples are convinced that "this is it," no one--with the exception of Jesus--gets the irony: this is indeed it! And how hard it must have been for him to accept their genuine rejoicing, their genuine praise, knowing that it would not last. In a few short days he will leave the Holy City, again accompanied by a crowd and shouts and yells, but this time the shouts and yells of a jeering mob and of Roman soldiers. And that is the second scene we encounter this morning.

It is the whole compass of human experience, wrapped into one short week. Triumph and disappointment, welcome and rejection, rejoicing and mourning, friendship and betrayal, gentleness and cruelty, love and hate, life in all its joy and death in all its finality.

During the course of Holy Week we will encounter in the Gospels of the Mass all these in what seems a maelstrom swirling about Jesus, all in the context of the Passover:

- On Monday, Mary will anoint his feet and Judas will reject him;

- On Tuesday Jesus will share his heartbreak with his disciples, who love him, and one will walk out the door, a sign to Jesus of his Father's call to glory;

- On Spy Wednesday, Judas will sell him out cheap, and they will celebrate the Passover;

- On Holy Thursday, Jesus makes himself their slave;

- On Good Friday he will offer himself as their Pascal Lamb.

It is overwhelming in its emotional weight. But even if we were to treat this simply as a story, for all the remarkable ironies, for all the emotional valence, what is most remarkable is the main character. Throughout the action, he alone remains steady, true to who he is, true to what he is about. Plots, treacheries, and defeats pile up in front of him, but he continues in his work. The darkness grows about him, but he remains light. Each of the major characters fudges, temporizes, denies and betrays everything he holds dear, but Jesus, if anything, becomes more and more truly who he is. He is simply and consistently Jesus, the true Son of his heavenly Father. And he simply and consistently continues to do his Father's will, what he has always been about (Luke 2:49).

Luke is remarkably clear about this as Jesus steers his course through all the shifts. His mien is, from beginning to end, marked with all of God's compassion. It is this, not vanity, that marks his reply to the Pharisees who complain about the Hosannas his disciples raise. It is compassion that draws him to this final Passover with his friends, that allows him to open his heart to them, that even allows him to pity the one will betray him and the one who will deny him.

Hence we find the most remarkable gestures as he makes his way along, gestures so in keeping with his character, so much so that we are not surprised. He heals the wounded servant's ear; he turns without bitterness to Peter as the cock crows; he responds with gentle insistence to his inquisitors; he does not revile his persecutors.

The singularity of his purpose--his purity of heart--grows, quite in contrast to the mendacity of the chief priests, the fickleness of Herod the great king, the squirming of the powerful Pilate. They, the seeming winners of this contest, look foolish as he takes up the opprobrium they lay upon him. He wears their contempt in the mocks and the blows and the spittle and the wounds they bestow upon him, but he is not made the less by them.

It comes to a crisis: as the nails are driven into his wrists, there is no cry of anguish but rather the most remarkable prayer: Father, forgive them, they do not know what they do.

As the crowd swirls around him, he alone remains fixed in place. Come down from that cross and save yourself, they cry. But he remains on the cross, unselfish to the end, to save us.

And to the very end, he points the true direction of it all.

A common criminal accepts him; he is greeted as the prodigal son is greeted (Luke 15:22-24).

The darkness grows unbearable; Jesus places his life completely, resolutely, in a quite final way into his Father's hands. It was what he had been doing all along. Now it is clear where it leads.

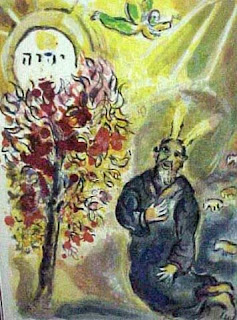

His is the very steadfastness of his Father, a faithfulness to who he is--even as the Lord explained himself to Moses: "The LORD, the LORD, a merciful and gracious God, slow to anger and rich in kindness and fidelity, continuing his kindness for a thousand generations, and forgiving wickedness and crime and sin..." (Exodus 34:6-7a).

His is the very steadfastness of his Father, a faithfulness to who he is--even as the Lord explained himself to Moses: "The LORD, the LORD, a merciful and gracious God, slow to anger and rich in kindness and fidelity, continuing his kindness for a thousand generations, and forgiving wickedness and crime and sin..." (Exodus 34:6-7a).

It is interesting, is it not, that the first words that he says to Peter in the Gospel of Mark, according to the scholars probably the first of the Gospels to be written down, are "Follow me" (Mark 1:17). And the last words he speaks in the Gospel of John, according to the scholars probably the last of the Gospels to be written down, are "Follow me" (John 21:22). The messages never falters. Peter does, but the Word does not! We do--sometimes often--but the Word does not!

He is the compass. He is true to the point. He shows us the way to true life, to life eternal. Even through the maelstrom.

It is hard to accept, even today. Perhaps harder. I recently read an article about some who claim that the line "Father, forgive them, for they know no what they do" should be expunged from the Gospel of Luke. In truth, the scholars acknowledge that it is a matter of controversy (Luke 23:34a, and note 5). But it is so consistent with the character of Jesus. For the truth is that all too frequently, we--we, the hard hearted, the manipulative, the Pharisees and Sadducees, the scribes--we know exactly what we are doing, but the Son of God leaves us totally disarmed; God knows more! This judgment of God is not mushy, not weak, not sentimental; it is the foolishness of God that is wiser than all the wisdom of men and women (1 Cor 1:25).

And we too live in the maelstrom. We have all read the reports from the great authorities of journalism--the New York Times, the BBC, the AP--who never hesitate to remind us how messy things can be, who never hesitate to question anyone or anything that tries point to a greater truth, especially if the person or the thing or the institution does not seem able bear the weight of the truth itself. It is overwhelming, confusing, brutal, disheartening. And that is even before we consider how messy, how confusing, how sinful our personal lives can become. And yet the Truth remains--greater than anyone of us indeed, greater than any crisis we, our world, even our church can face--still always calling, still always commanding: "Follow me."

He is the compass. He is true to the point. He shows us the way to true life, to life eternal. Even through the maelstrom.

It is hard to accept, even today. Perhaps harder. I recently read an article about some who claim that the line "Father, forgive them, for they know no what they do" should be expunged from the Gospel of Luke. In truth, the scholars acknowledge that it is a matter of controversy (Luke 23:34a, and note 5). But it is so consistent with the character of Jesus. For the truth is that all too frequently, we--we, the hard hearted, the manipulative, the Pharisees and Sadducees, the scribes--we know exactly what we are doing, but the Son of God leaves us totally disarmed; God knows more! This judgment of God is not mushy, not weak, not sentimental; it is the foolishness of God that is wiser than all the wisdom of men and women (1 Cor 1:25).

And we too live in the maelstrom. We have all read the reports from the great authorities of journalism--the New York Times, the BBC, the AP--who never hesitate to remind us how messy things can be, who never hesitate to question anyone or anything that tries point to a greater truth, especially if the person or the thing or the institution does not seem able bear the weight of the truth itself. It is overwhelming, confusing, brutal, disheartening. And that is even before we consider how messy, how confusing, how sinful our personal lives can become. And yet the Truth remains--greater than anyone of us indeed, greater than any crisis we, our world, even our church can face--still always calling, still always commanding: "Follow me."

He is the compass. His is the way.

AMDG